By Katharine Ridenhour, Director of Advertising

Social media influencers are easy to identify. They share their life on social media (mostly Instagram) with expertly crafted posts that are designed to engage their many, many followers. But they’re not just curating likes – these individuals can make millions on brand partnerships. According to NPR, brands are expected to spend up to $10 billion next year on social media influencers.

Engaging popular individuals to market a brand isn’t new territory. Companies have been hiring famous brand ambassadors in order to gain favor with the celebrities’ fans for almost as long as advertising has been around. And with the advent of social media, you didn’t have to be a star to influence public opinion – anyone with enough savvy could become an influencer.

Now, they don’t even have to be real.

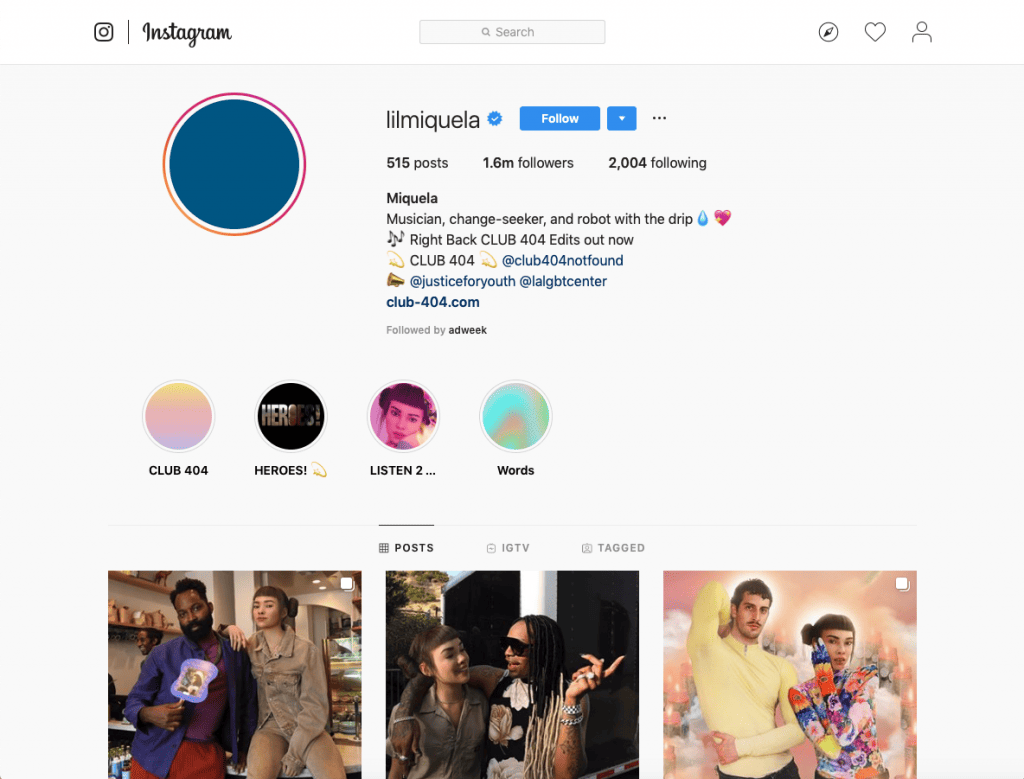

This past week, the New York Times shared a story about virtual influencers whose traits were carefully selected to be most appealing to Instagram users. The best example is Miquela Sousa – a computer-generated influencer with 1.6 million followers and multiple brand deals. She’s worked with big names like Prada and Samsung, given interviews from Coachella and appeared in a Calvin Klein commercial alongside supermodel Bella Hadid.

Our team had so many questions. Do people know she’s not real? Why would people follow her? How are brands paying her to share their products? Better yet, who’s getting paid?

Our team was so curious we had to research at least the answerable questions. Turns out, the company who created Miquela is named Brud, and initially they wouldn’t reveal their identity. They are pocketing the money from brands interested in promoting with Miquela. Brud’s website is a Google Doc with little information – but in their short FAQ, when asked if Miquela is real, their answer is “as real as Rihanna.”

Digital is like the Wild West – there are no rules and we’re all figuring it out as we go. But outside of any potential legal questions, how can brands know when a line has been crossed ethically?

There’s already been questions about this that have brought about change in how influencers share paid content. You may have noticed #ad on posts – influencers now use the hashtag to alert followers if they were paid to share.

But what about when the influencer isn’t a person at all?

Is this simply another example of brands creating a character spokesperson, like KFC with Colonel Sanders or Disney with Mickey Mouse?

To us, this feels more ethically grey. Unlike typical influencers, Miquela can’t stand behind the products she’s promoting. She doesn’t wear clothes, she doesn’t use cell phones, she isn’t experiencing music festivals. It could be argued that the characters above don’t use the product/service they are promoting, but it’s also incredibly evident they are a product of the brand. In the case of Miquela, or any other virtual influencer, it’s much less obvious that these influencers are, put simply, more characters that have been created to sell a product.

There isn’t a clear answer for moving forward. As AI, robots and virtual reality continue to improve, the lines will continue to get blurrier. The best thing brands can do is move cautiously and transparently. Ethics aside, what will ultimately determine if virtual influencers endure is the same thing all marketing comes down to – whether it works.